An overwhelming election victory promises to reshape Indian politics.

INDIA brims with colorful politicians, but none has quite the sense of political theatre of Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). He swept into Varanasi, India’s most ancient city, on May 17th pledging to clean the Ganges, its holiest and filthiest river. Three days later, in Delhi, BJP parliamentarians chanted and roared unanimous support for him, and he broke down in tears in mid-speech. After that he called on India’s president, Pranab Mukherjee, who agreed to swear him in as India’s 14th prime minister on May 26th.

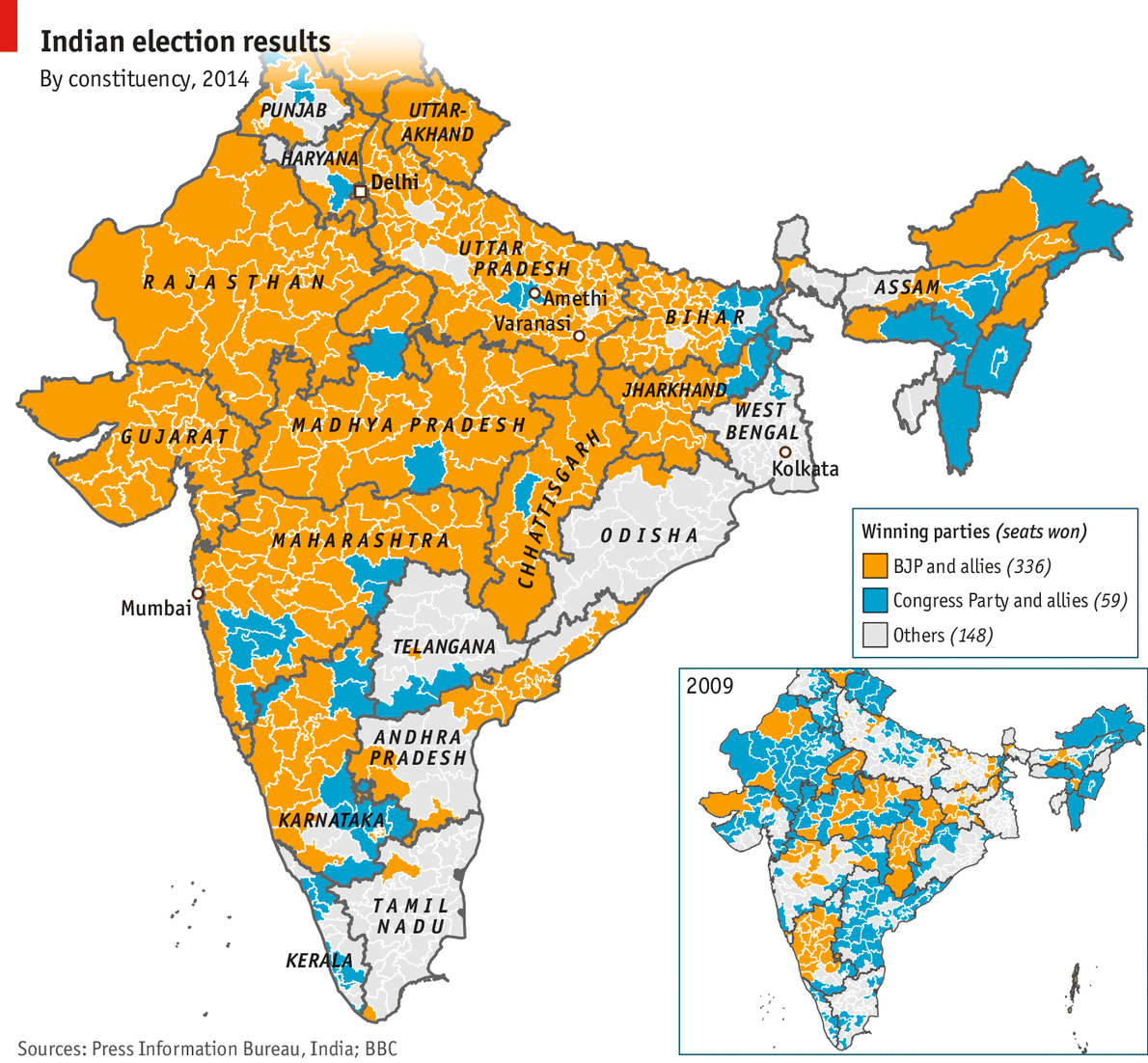

Mr. Modi won the election by a margin almost nobody imagined possible. Last year he spoke of an aandhi, a “storm blowing in our favour”. The storm broke, marking a national political shift as big as any since independence in 1947. Mr. Modi smashed the long domination of Congress. In no previous national election had any single party got more votes than Congress; this time the BJP stunned its rival, winning 31% of the votes to Congress’s 19%. No single party other than Congress had ever before won an outright parliamentary majority; this time the BJP alone took 282 of 543 seats (see map). Add its closest allies in the National Democratic Alliance and the tally is a handsome 336. Congress got just 44.

Mr. Modi’s victory has disproved an article of political faith from the past three decades: that India’s messy democracy, cursed by strong regional and caste-based parties, could produce only fragmented outcomes and weak coalition governments. This, the clearest result since 1984, should mean stable, decisive and predictable rule. Mr. Modi, not one to hold back, hints at being in office for a decade or more.

The scale of Congress’s defeat means that is no idle ambition. In Amethi, the Uttar Pradesh (UP) constituency of Rahul Gandhi, Congress’s young leader, voters sharply cuttheir MP’s once-huge margin of victory. Villagers there said they wanted economic development, not feudal charity. Everyone had expected Congress to slump to a historic low,

but its collapse is so complete that some doubt it can even act as an opposition. Mr Gandhi and his mother, Sonia, gracelessly failed to congratulate Mr Modi. Their perfunctory offers to quit party posts on May 19th were refused by Congress sycophants. None of that suggests a party ready to learn from failure.

But in this election Mr Modi has accomplished much more than just the defeat of Congress. In Varanasi, where he was elected as MP, he flattened the anti-corruption campaigner, Arvind Kejriwal. Mr Kejriwal’s Aam Aadmi Party got only four seats nationally, all in Punjab. That suggests it was a blunder to seek a David-versus-Goliath clash with Mr Modi: sometimes Goliath wins.

Mr. Modi was also in Varanasi to relish his success throughout UP, a backwaed state of 207m, where the BJP swept 71 out of 80 seats. Along with 22 out of 40 seats from neighbouring Bihar, this was the core of the BJP's national victory. Triumph gave the lie to the idea that the party won only because of voter's grumpiness at the national misrule of Congress: in these states it had to wallop regional parties, as Congress has long been sidelined there.

The fate of those regional parties was instructive. BJP strategists outplayed them. UP's biggest loser was Mayawati of the Bahujan Samaj Party dominated by dalits, previously “untouchables”. She got a fifth of votes cast in the state, and the third-biggest share nationally, but the first-past-the-post electoral system ensured that her party won no seats. The BJP translated popularity into power with historic efficiency, needing an average of only 600,000 votes for every seat won. Hapless Congress averaged 2.4m votes per seat, the Aam Aadmi Party needed 2.8m.

In Bihar the battered regional leader, Nitish Kumar, quit as chief minister on May 17th. Once lauded as a potential national leader and a responsive figure who brought big development gains, his fall since breaking an alliance with the BJP in 2013 has been precipitous.

Yet regional parties were not uniformly in retreat. Collectively they still got about half of all votes, as they have since the 1990s. Some fared spectacularly. The party of the chief minister of Odisha (formerly Orissa), Naveen Patnaik, took 20 of 21 seats and a fourth successive victory in concurrent state elections. In southern Tamil Nadu, the party of Jayaram Jayalalitha, its chief minister, quadrupled its tally to 37 of 39 seats. Mamata Banerjee, who rules in West Bengal, got 34 of 42 seats. In the newly split states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana local parties now hold sway.

Modi’s operandi

What explains the BJP’s sweeping success? The answer matters: misreading previous election results led Congress to make poor policy choices. It mistakenly thought voters in 2004 had not cared about economic growth (in fact they had, but Congress won thanks to quirks in alliance politics). After winning in 2009 Congress deluded itself that promises of rural welfare had brought victory, when in fact it was job-hungry urban voters who put their faith in Manmohan Singh, the outgoing prime minister. Neglect since of young, aspiring town-dwelling voters cost Congress most.

There are many reasons why Mr Modi won so convincingly. His slick, expensive campaign shaped local media coverage: the BJP will not say, but it probably spent $1 billion. He is a gifted public speaker, vocal and strong. An outsider, he brings an enthralling story of rising from being a mere tea-seller’s son. His lowish caste, as an “Other Backward Class”, played well, especially in caste-obsessed UP.

Hindutva, a doctrine of Hindu supremacy, also counted, appealing to voters proud of their heritage and often antagonistic to Muslims. Mr Modi mostly eschewed anti-Muslim language, aside from barbs at Bangladeshi “infiltrators”. But his credibility among the Hindu right was long ago established, so he needed do little more than devote attention to Varanasi and “maa Ganga” (mother Ganges), or pose with a big portrait of Lord Ram near the controversial site of a ruined mosque.

Hindu nationalist volunteers from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), to which Mr. Modi has belonged since childhood, also helped, lifting overall turnout to a record 554m, or 66%. Meanwhile Mr. Modi made no special effort for religious minorities. Just seven of 482 BJP candidates were Muslim, and none won. The new Parliament has fewer Muslim MPs than any since 1952.

For all that, it was Mr. Modi’s talk of vikas (development), that guided the campaign. That chimed with a widespread yearning for prosperity. In every speech Mr. Modi listed practical gains that flowed from his rule in Gujarat: reliable power and water, decent roads, flourishing industry, less of the most corrosive forms of graft. Voters who chanted “Modi, Modi, Modi” often said that one word, “Gujarat”, signified their hopes for similar material gains.

The BJP’s cheery slogan, “Good times ahead” captured such hope. Mr. Modi has used it since the election, too. Addressing Parliament on May 20th, he spoke of being judged on his record at the next election in 2019, especially on helping the poor, saying: “I want to tell India we must be optimistic.” Mr. Modi knows that electoral fortunes can swing fast, but voters reward governments that get results. He was elected three times in Gujarat. The first time, in 2002, he won on the back of Hindu nationalism after communal riots that killed over 1,000. The next two successes came mostly by bringing about development.

What’s good for Gujarat…

His challenge as prime minister is to prove that he can get decisive and efficient government out of a political system long unable to get things done. Perhaps that is why he has offered “absolute co-operation” to sympathetic parties, seeking a broad coalition, for example to get legislation through Parliament’s upper house, where the BJP has only 48 of 243 seats.

Those inclusive intentions may clash with his leadership style—“authoritarian”, says a sympathetic journalist in Gujarat. By instinct Mr. Modi centralizes power, so his prime minister’s office will be mightier than its recent predecessors. He may install a slim cabinet packed with technocrats. Those close to him say he behaves as a chief executive, setting ministers and senior bureaucrats tasks with deadlines and expecting them to report back on time. Speaking in Parliament on May 20th, he advised his colleagues—furiously lobbying for cabinet jobs—that what counts more are the tasks they complete, not the positions they hold. Corporate India likes the sound of that; some are comparing him to Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew.

An autocratic style could also clash with a second ambition, to let states’ chief ministers have a greater say in policymaking and implementation. Mr. Modi needs co-operation from pro-business and reformist chief ministers—for example Chandrababu Naidu, back in Andhra Pradesh—to resolve problems, such as the provision of land, that have bedevilled efforts to improve infrastructure. States could soften labour laws, say, to encourage manufacturers to expand. Reformists might also redirect a big rural jobs scheme to the tasks of building dams and roads instead of merely using it as welfare.

In one area, foreign policy, early signs of dynamism are apparent. South Asian leaders, including Pakistan’s prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, have been invited to the prime minister’s swearing-in on May 26th. Mr. Sharif was notably quick to congratulate Mr. Modi on his win, and last year invited Manmohan Singh to his own inauguration. He might struggle to persuade Pakistan’s anxious army to let him travel to see Mr. Modi so early. Either way, there are encouraging signs that Mr. Modi’s team is open to engagement, despite the killing of an Indian soldier in Kashmir this week. More modestly hopeful were noises from China, where a think-tank described Mr Modi as “like Nixon”, a complimentary reference to the former president’s friendliness to Beijing, rather than to Watergate.

China, however, will be less cheered by Mr. Modi’s gushing goodwill towards Japan. He described his “wonderful experience” working with the country when he was chief minister, his gratitude towards Shinzo Abe, its prime minister, and expectations of a strong “mutual strategic partnership”. Japan, unlike America and Europe, preserved friendly ties with Mr. Modi even after the riots in Gujarat in 2002. Japan, too, could be a source of the investment that Mr. Modi needs for his infrastructure overhaul. He also spoke to America’s president, Barack Obama, which might help ease a recent diplomatic spat between the two countries.

Foreign-policy figures say an early priority will be building strong relations in Asia. That is partly because economic plans are expected to do most to determine Mr. Modi’s international efforts. He is short of foreign experience, but at least as chief minister in Gujarat he made much play of welcoming foreign firms. He also took occasional trips—notably to Japan and China—to seek more trade and investment.

If outsiders seek a high-profile project to win his favour, one option would be to offer help with his promise to clean the Ganges. That requires building new sewage systems in dozens of towns and cities on its banks, closing tanneries and factories, and getting state governments to co-operate. An emotional Mr. Modi made cleaning the river a test of his leadership. He has five years to prove himself.

No comments:

Post a Comment